How the use of brain imaging is furthering our understanding of Lupus

In this blog Michelle discusses her research into neurocognitive function in patients with lupus.

That wasn’t anywhere near as bad as I thought.

This is something I often hear from participants taking part in research.

The department I work in is very research active and many patients are interested in helping with the studies we are undertaking. We are always incredibly grateful for their time and interest in the research. One of the main motivators for volunteers is knowing that they may be able to help improve treatment for loved ones or future patients.

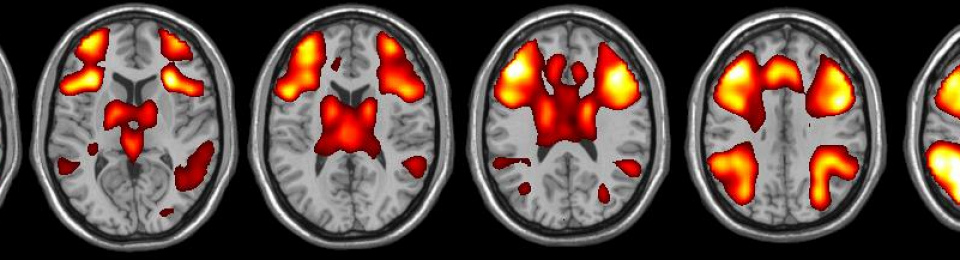

Our latest study is investigating how the brain works in people with Lupus, specifically looking at memory and concentration problems. To do this we need the help of volunteers with Lupus, as well as people without. Each participant undergoes a five-hour research visit, during which we collect lots of data as well as scanned images of the brain.

Participants are scanned using a technique called functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). The MRI machine, based at the NIHR / WT Manchester Clinical Research Facility, is essentially a giant magnet (70,000 times the earth’s magnetic field) that provides a non-invasive way to look at the brain. During the scan participants complete a series of memory and emotion tasks that provide data for our study about how the brain works in people with Lupus.

Participants lie on the bed and are moved into the machine. As we are conducting “functional” imaging, looking at how the brain is responding to stimuli over time, we run tasks while the participant is in the scanner.

Using a series of mirrors, participants are able to see a screen that it set up at the end of the scanner. The screen provides the information needed for participants to complete a memory task and an emotion task, with participants responding to images and questions using a button box that’s with them in the scanner.

While the participant completes the tasks, the scanner measures signals in their brain. We can then match these signals to the tasks, and build a picture of how their memory and emotional processing works. Comparisons can then be made between brain signals in people with and without Lupus.

All of this will help us to better understand how the brain works in Lupus and what effects active disease in Lupus can have on memory. Hopefully this will eventually enable us to test new treatments designed to improve memory problems in Lupus.

Without the help of research volunteers, we wouldn’t be able to further our understanding. We’re very grateful for every participant’s help.

For further information about the study, contact Michelle Barraclough on michelle.barraclough@manchester.ac.uk. We are still recruiting, but hope to have the final results ready by December 2016.